day 1: getting started with python¶

- overview of day 1

- section 1.3.1 tabular data

- section 1.3.2 subset

- section 1.3.3 summarize

- mindset: excel on steroids

section 1.3.1: tables¶

- mindset: excel on steroids

- file system, folders, csv files

- checking, cleaning, summarizing

- sql-like operations on datasets

- combination of numeric and text

- intro to day 2, nlp and spacy

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

# df = pd.read_csv('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/mwaskom/seaborn-data/master/iris.csv')

df = sns.load_dataset('iris')

df.head()

df.to_csv("csv/iris.csv", sep="\t", header=True, index=False)

# file path on google colab

fp = '/content/iris.csv'

# file path relative to local working dir

fp = '../../csv/iris.csv'

df = pd.read_csv(fp, sep="\t", header=0)

df.head()

Instructor notes¶

Estimated teaching time: 30 min

Estimated challenge time: 30 min

Key questions:

- "How can I import data in Python ?"

- "What is Pandas ?"

- "Why should I use Pandas to work with data ?"

Learning objectives:

- "Navigate the workshop directory and download a dataset."

- "Explain what a library is and what libraries are used for."

- "Describe what the Python Data Analysis Library (Pandas) is."

- "Load the Python Data Analysis Library (Pandas)."

- "Use

read_csvto read tabular data into Python." - "Describe what a DataFrame is in Python."

- "Access and summarize data stored in a DataFrame."

- "Define indexing as it relates to data structures."

- "Perform basic mathematical operations and summary statistics on data in a Pandas DataFrame."

- "Create simple plots."

Automating data analysis tasks in Python¶

We can automate the process of performing data manipulations in Python. It's efficient to spend time building the code to perform these tasks because once it's built, we can use it over and over on different datasets that use a similar format. This makes our methods easily reproducible. We can also easily share our code with colleagues and they can replicate the same analysis.

The Dataset¶

For this lesson, we will be using the Portal Teaching data, a subset of the data from Ernst et al Long-term monitoring and experimental manipulation of a Chihuahuan Desert ecosystem near Portal, Arizona, USA

We will be using this dataset, which can be downloaded here: surveys.csv ... but don't click to download it in your browser - we are going to use Python !

import urllib.request

# You can also get this URL value by right-clicking the `surveys.csv` link above and selecting "Copy Link Address"

url = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/nils-holmberg/sfac-py/main/csv/surveys.csv'

# save file

urllib.request.urlretrieve(url, 'tmp/surveys.csv')

If Jupyter is running locally on your computer, you'll now have a file surveys.csv in the current working directory.

You can check by clicking on File tab on the top left of the notebook to see if the file exists. If you are running Jupyter on a remote server or cloud service (eg Colaboratory or Azure Notebooks), the file will be there instead.

We are studying the species and weight of animals caught in plots in our study

area. The dataset is stored as a .csv file: each row holds information for a

single animal, and the columns represent:

| Column | Description |

|---|---|

| record_id | Unique id for the observation |

| month | month of observation |

| day | day of observation |

| year | year of observation |

| site_id | ID of a particular plot |

| species_id | 2-letter code |

| sex | sex of animal ("M", "F") |

| hindfoot_length | length of the hindfoot in mm |

| weight | weight of the animal in grams |

The first few rows of our file look like this:

record_id,month,day,year,site_id,species_id,sex,hindfoot_length,weight

1,7,16,1977,2,NL,M,32,

2,7,16,1977,3,NL,M,33,

3,7,16,1977,2,DM,F,37,

4,7,16,1977,7,DM,M,36,

5,7,16,1977,3,DM,M,35,

6,7,16,1977,1,PF,M,14,

7,7,16,1977,2,PE,F,,

8,7,16,1977,1,DM,M,37,

9,7,16,1977,1,DM,F,34,About Libraries¶

A library in Python contains a set of tools (called functions) that perform tasks on our data. Importing a library is like getting a piece of lab equipment out of a storage locker and setting it up on the bench for use in a project. Once a library is set up, it can be used or called to perform many tasks.

If you have noticed in the previous code import urllib.request, we are calling

a request function from library urllib to download our dataset from web.

Pandas in Python¶

The dataset we have, is in table format. One of the best options for working with tabular data in Python is to use the Python Data Analysis Library (a.k.a. Pandas). The Pandas library provides data structures, produces high quality plots with matplotlib and integrates nicely with other libraries that use NumPy (which is another Python library) arrays.

First, lets make sure the Pandas and matplotlib packages are installed.

#conda install pandas matplotlib

Python doesn't load all of the libraries available to it by default. We have to

add an import statement to our code in order to use library functions. To import

a library, we use the syntax import libraryName. If we want to give the

library a nickname to shorten the command, we can add as nickNameHere. An

example of importing the pandas library using the common nickname pd is below.

import pandas as pd

# read data

#df = pd.read_csv('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/mwaskom/seaborn-data/master/iris.csv')

#df = pd.read_csv(fp, sep="\t", header=0)

Each time we call a function that's in a library, we use the syntax

LibraryName.FunctionName. Adding the library name with a . before the

function name tells Python where to find the function. In the example above, we

have imported Pandas as pd. This means we don't have to type out pandas each

time we call a Pandas function.

Reading CSV Data Using Pandas¶

We will begin by locating and reading our survey data which are in CSV format. CSV stands for Comma-Separated Values and is a common way store formatted data. Other symbols my also be used, so you might see tab-separated, colon-separated or space separated files. It is quite easy to replace one separator with another, to match your application. The first line in the file often has headers to explain what is in each column. CSV (and other separators) make it easy to share data, and can be imported and exported from many applications, including Microsoft Excel.

We can use Pandas' read_csv function to pull the file directly into a

DataFrame.

So What's a DataFrame?¶

A DataFrame is a 2-dimensional data structure that can store data of different

types (including characters, integers, floating point values, factors and more)

in columns. It is similar to a spreadsheet or an SQL table or the data.frame in

R. A DataFrame always has an index (0-based). An index refers to the position of

an element in the data structure.

# note that pd.read_csv is available because we imported pandas as pd, and data is available where we saved it

df = pd.read_csv("tmp/surveys.csv")

df.head()

The above command outputs a DateFrame object, which Jupyter displays as a table (snipped in the middle since there are many rows).

We can see that there were 33,549 rows parsed. Each row has 9

columns. The first column is the index of the DataFrame. The index is used to

identify the position of the data, but it is not an actual column of the DataFrame.

It looks like the read_csv function in Pandas read our file properly. However,

we haven't saved any data to memory so we can work with it.We need to assign the

DataFrame to a variable. Remember that a variable is a name for a value, such as x,

or data. We can create a new object with a variable name by assigning a value to it using =.

Let's call the imported survey data surveys_df:

surveys_df = pd.read_csv("../../csv/surveys.csv")

Notice when you assign the imported DataFrame to a variable, Python does not

produce any output on the screen. We can view the value of the surveys_df

object by typing its name into the cell.

surveys_df

which prints contents like above.

You can also select just a few rows, so it is easier to fit on one window, you can see that pandas has neatly formatted the data to fit our screen.

Here, we will be using a function called head.

The head() function displays the first several lines of a file. It is discussed below.

surveys_df.head()

Exploring Our Species Survey Data¶

Again, we can use the type function to see what kind of thing surveys_df is:

type(surveys_df)

As expected, it's a DataFrame (or, to use the full name that Python uses to refer

to it internally, a pandas.core.frame.DataFrame).

What kind of things does surveys_df contain? DataFrames have an attribute

called dtypes that answers this:

surveys_df.dtypes

All the values in a single column have the same type. For example, months have type

int64, which is a kind of integer. Cells in the month column cannot have

fractional values, but the weight and hindfoot_length columns can, because they

have type float64. The object type doesn't have a very helpful name, but in

this case it represents strings (such as 'M' and 'F' in the case of sex).

Useful Ways to View DataFrame objects in Python¶

There are many ways to summarize and access the data stored in DataFrames, using attributes and methods provided by the DataFrame object.

To access an attribute, use the DataFrame object name followed by the attribute

name df_object.attribute. Using the DataFrame surveys_df and attribute

columns, an index of all the column names in the DataFrame can be accessed

with surveys_df.columns.

Methods are called in a similar fashion using the syntax df_object.method().

As an example, surveys_df.head() gets the first few rows in the DataFrame

surveys_df using the head() method. With a method, we can supply extra

information in the parens to control behaviour.

Let's look at the data using these.

Challenge - DataFrames¶

Using our DataFrame surveys_df, try out the attributes & methods below to see

what they return.

surveys_df.columnssurveys_df.shapeTake note of the output ofshape- what format does it return the shape of the DataFrame in? HINT: More on tuples, here.surveys_df.head()Also, what doessurveys_df.head(15)do?surveys_df.tail()

Solution - DataFrames¶

... try it yourself !

Calculating Statistics From Data¶

We've read our data into Python. Next, let's perform some quick summary statistics to learn more about the data that we're working with. We might want to know how many animals were collected in each plot, or how many of each species were caught. We can perform summary stats quickly using groups. But first we need to figure out what we want to group by.

Let's begin by exploring our data:

# Look at the column names

surveys_df.columns

Let's get a list of all the species. The pd.unique function tells us all of

the unique values in the species_id column.

pd.unique(surveys_df['species_id'])

Challenge - Statistics¶

Create a list of unique site ID's found in the surveys data. Call it

site_names. How many unique sites are there in the data? How many unique species are in the data?What is the difference between

len(site_names)andsurveys_df['site_id'].nunique()?

Solution - Statistics¶

site_names = pd.unique(surveys_df['site_id'])

print(len(site_names), surveys_df['site_id'].nunique())

Groups in Pandas¶

We often want to calculate summary statistics grouped by subsets or attributes within fields of our data. For example, we might want to calculate the average weight of all individuals per site.

We can calculate basic statistics for all records in a single column using the syntax below:

surveys_df['weight'].describe()

We can also extract one specific metric if we wish:

surveys_df['weight'].min()

surveys_df['weight'].max()

surveys_df['weight'].mean()

surveys_df['weight'].std()

# only the last command shows output below - you can try the others above in new cells

surveys_df['weight'].count()

But if we want to summarize by one or more variables, for example sex, we can

use Pandas' .groupby method. Once we've created a groupby DataFrame, we

can quickly calculate summary statistics by a group of our choice.

# Group data by sex

grouped_data = surveys_df.groupby('sex')

The pandas function describe will return descriptive stats including: mean,

median, max, min, std and count for a particular column in the data. Note Pandas'

describe function will only return summary values for columns containing

numeric data.

# Summary statistics for all numeric columns by sex

grouped_data.describe()

# Provide the mean for each numeric column by sex

# As above, only the last command shows output below - you can try the others above in new cells

grouped_data.mean()

The groupby command is powerful in that it allows us to quickly generate

summary stats.

Challenge - Summary Data¶

- How many recorded individuals are female

Fand how many maleM- A) 17348 and 15690

- B) 14894 and 16476

- C) 15303 and 16879

- D) 15690 and 17348

- What happens when you group by two columns using the following syntax and

then grab mean values:

grouped_data2 = surveys_df.groupby(['site_id','sex'])grouped_data2.mean()

- Summarize weight values for each site in your data. HINT: you can use the

following syntax to only create summary statistics for one column in your data

by_site['weight'].describe()

Solution- Summary Data¶

## Solution Challenge 1

grouped_data.count()

Solution - Challenge 2¶

The mean value for each combination of site and sex is calculated. Remark that the mean does not make sense for each variable, so you can specify this column-wise: e.g. I want to know the last survey year, median foot-length and mean weight for each site/sex combination:

# Solution- Challenge 3

surveys_df.groupby(['site_id'])['weight'].describe()

Did you get #3 right?¶

A Snippet of the Output from part 3 of the challenge looks like:

site_id

1 count 1903.000000

mean 51.822911

std 38.176670

min 4.000000

25% 30.000000

50% 44.000000

75% 53.000000

max 231.000000

...Quickly Creating Summary Counts in Pandas¶

Let's next count the number of samples for each species. We can do this in a few

ways, but we'll use groupby combined with a count() method.

# Count the number of samples by species

species_counts = surveys_df.groupby('species_id')['record_id'].count()

print(species_counts)

Or, we can also count just the rows that have the species "DO":

surveys_df.groupby('species_id')['record_id'].count()['DO']

Basic Math Functions¶

If we wanted to, we could perform math on an entire column of our data. For example let's multiply all weight values by 2. A more practical use of this might be to normalize the data according to a mean, area, or some other value calculated from our data.

# Multiply all weight values by 2 but does not change the original weight data

surveys_df['weight']*2

Indexing, Slicing and Subsetting¶

Estimated teaching time: 30 min

Estimated challenge time: 30 min

Key questions:

- "How can I access specific data within my data set?"

- "How can Python and Pandas help me to analyse my data?"

Learning objectives:

- Describe what 0-based indexing is.

- Manipulate and extract data using column headings and index locations.

- Employ slicing to select sets of data from a DataFrame.

- Employ label and integer-based indexing to select ranges of data in a dataframe.

- Reassign values within subsets of a DataFrame.

- Create a copy of a DataFrame.

- "Query /select a subset of data using a set of criteria using the following operators: =, !=, >, <, >=, <=."

- Locate subsets of data using masks.

- Describe BOOLEAN objects in Python and manipulate data using BOOLEANs.

In this lesson, we will explore ways to access different parts of the data in a Pandas DataFrame using:

- Indexing,

- Slicing, and

- Subsetting

Indexing, Slicing and Subsetting¶

In this lesson, we will explore ways to access different parts of the data in a Pandas DataFrame using:

- Indexing,

- Slicing, and

- Subsetting

Loading our data¶

We will continue to use the surveys dataset that we worked with in the last lesson. Let's reopen and read in the data again:

# Make sure pandas is loaded

import pandas as pd

# Read in the survey CSV

surveys_df = pd.read_csv("tmp/surveys.csv")

Indexing and Slicing in Python¶

We often want to work with subsets of a DataFrame object. There are different ways to accomplish this including: using labels (column headings), numeric ranges, or specific x,y index locations.

Selecting data using Labels (Column Headings)¶

We use square brackets [] to select a subset of an Python object. For example,

we can select all data from a column named species_id from the surveys_df

DataFrame by name. There are two ways to do this:

# Method 1: select a 'subset' of the data using the column name

surveys_df['species_id'].head()

# Method 2: use the column name as an 'attribute'; gives the same output

surveys_df.species_id.head()

We can also create a new object that contains only the data within the

species_id column as follows:

# Creates an object, surveys_species, that only contains the `species_id` column

surveys_species = surveys_df['species_id']

We can pass a list of column names too, as an index to select columns in that order. This is useful when we need to reorganize our data.

NOTE: If a column name is not contained in the DataFrame, an exception (error) will be raised.

# Select the species and plot columns from the DataFrame

surveys_df[['species_id', 'site_id']].head()

What happens if you ask for a column that doesn't exist?

surveys_df['speciess']

Outputs:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

/Applications/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/pandas/core/indexes/base.py in get_loc(self, key, method, tolerance)

2392 try:

-> 2393 return self._engine.get_loc(key)

2394 except KeyError:

pandas/_libs/index.pyx in pandas._libs.index.IndexEngine.get_loc (pandas/_libs/index.c:5239)()

pandas/_libs/index.pyx in pandas._libs.index.IndexEngine.get_loc (pandas/_libs/index.c:5085)()

pandas/_libs/hashtable_class_helper.pxi in pandas._libs.hashtable.PyObjectHashTable.get_item (pandas/_libs/hashtable.c:20405)()

pandas/_libs/hashtable_class_helper.pxi in pandas._libs.hashtable.PyObjectHashTable.get_item (pandas/_libs/hashtable.c:20359)()

KeyError: 'speciess'

During handling of the above exception, another exception occurred:

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-7-7d65fa0158b8> in <module>()

1

2 # What happens if you ask for a column that doesn't exist?

----> 3 surveys_df['speciess']

4

/Applications/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/pandas/core/frame.py in __getitem__(self, key)

2060 return self._getitem_multilevel(key)

2061 else:

-> 2062 return self._getitem_column(key)

2063

2064 def _getitem_column(self, key):

/Applications/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/pandas/core/frame.py in _getitem_column(self, key)

2067 # get column

2068 if self.columns.is_unique:

-> 2069 return self._get_item_cache(key)

2070

2071 # duplicate columns & possible reduce dimensionality

/Applications/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/pandas/core/generic.py in _get_item_cache(self, item)

1532 res = cache.get(item)

1533 if res is None:

-> 1534 values = self._data.get(item)

1535 res = self._box_item_values(item, values)

1536 cache[item] = res

/Applications/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/pandas/core/internals.py in get(self, item, fastpath)

3588

3589 if not isnull(item):

-> 3590 loc = self.items.get_loc(item)

3591 else:

3592 indexer = np.arange(len(self.items))[isnull(self.items)]

/Applications/anaconda/lib/python3.6/site-packages/pandas/core/indexes/base.py in get_loc(self, key, method, tolerance)

2393 return self._engine.get_loc(key)

2394 except KeyError:

-> 2395 return self._engine.get_loc(self._maybe_cast_indexer(key))

2396

2397 indexer = self.get_indexer([key], method=method, tolerance=tolerance)

pandas/_libs/index.pyx in pandas._libs.index.IndexEngine.get_loc (pandas/_libs/index.c:5239)()

pandas/_libs/index.pyx in pandas._libs.index.IndexEngine.get_loc (pandas/_libs/index.c:5085)()

pandas/_libs/hashtable_class_helper.pxi in pandas._libs.hashtable.PyObjectHashTable.get_item (pandas/_libs/hashtable.c:20405)()

pandas/_libs/hashtable_class_helper.pxi in pandas._libs.hashtable.PyObjectHashTable.get_item (pandas/_libs/hashtable.c:20359)()

KeyError: 'speciess'

Python tells us what type of error it is in the traceback, at the bottom it says KeyError: 'speciess' which means that speciess is not a column name (or Key in the related python data type dictionary).

# What happens when you flip the order?

surveys_df[['site_id', 'species_id']].head()

Extracting Range based Subsets: Slicing¶

REMINDER: Python Uses 0-based Indexing

Let's remind ourselves that Python uses 0-based indexing. This means that the first element in an object is located at position

- This is different from other tools like R and Matlab that index elements within objects starting at 1.

# Create a list of numbers:

a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Challenge - Extracting data¶

What value does the code a[0] return?

How about this: a[5]

In the example above, calling

a[5]returns an error. Why is that?What about a[len(a)] ?

Solutions - Extracting data¶

a[0]

# Solution #2

# a[5]

Solution #2¶

In above example, the error says list index out of range. This means we don't have index 5 in our list. The maximum index for a is 4, as indexing starts at 0.

# Solution #3

# a[len(a)]

Solution - # 4 - Extracting data¶

This also gives an error, because len(a) is 5 which is not the maximum index

Slicing Subsets of Rows in Python¶

Slicing using the [] operator selects a set of rows and/or columns from a

DataFrame. To slice out a set of rows, you use the following syntax:

data[start:stop]. When slicing in pandas the start bound is included in the

output. The stop bound is one step BEYOND the row you want to select. So if you

want to select rows 0, 1 and 2 your code would look like this with our surveys data:

# Select rows 0, 1, 2 (row 3 is not selected)

surveys_df[0:3]

The stop bound in Python is different from what you might be used to in languages like Matlab and R.

Now lets select the first 5 rows (rows 0, 1, 2, 3, 4).

surveys_df[:5]

# Select the last element in the list

# (the slice starts at the last element, and ends at the end of the list)

surveys_df[-1:]

We can also reassign values within subsets of our DataFrame.

Let's create a brand new clean dataframe from the original data CSV file.

surveys_df = pd.read_csv("surveys.csv")

Slicing Subsets of Rows and Columns in Python¶

We can select specific ranges of our data in both the row and column directions using either label or integer-based indexing.

locis primarily label based indexing. Integers may be used but they are interpreted as a label.ilocis primarily integer based indexing

To select a subset of rows and columns from our DataFrame, we can use the

iloc method. For example, we can select month, day and year (columns 2, 3

and 4 if we start counting at 1), like this:

iloc[row slicing, column slicing]

surveys_df.iloc[0:3, 1:4]

Notice that we asked for a slice from 0:3. This yielded 3 rows of data. When you ask for 0:3, you are actually telling Python to start at index 0 and select rows 0, 1, 2 up to but not including 3.

Let's explore some other ways to index and select subsets of data:

# Select all columns for rows of index values 0 and 10

surveys_df.loc[[0, 10], :]

# What does this do?

surveys_df.loc[0, ['species_id', 'site_id', 'weight']]

# What happens when you type the code below?

surveys_df.loc[[0, 10, 35549], :]

NOTE: Labels must be found in the DataFrame or you will get a KeyError.

Indexing by labels loc differs from indexing by integers iloc.

With loc, the both start bound and the stop bound are inclusive. When using

loc, integers can be used, but the integers refer to the

index label and not the position. For example, using loc and select 1:4

will get a different result than using iloc to select rows 1:4.

We can also select a specific data value using a row and

column location within the DataFrame and iloc indexing:

# Syntax for iloc indexing to finding a specific data element

dat.iloc[row, column]

In following iloc example:

surveys_df.iloc[2, 6]

Remember that Python indexing begins at 0. So, the index location [2, 6] selects the element that is 3 rows down and 7 columns over in the DataFrame.

Challenge - Range¶

What happens when you execute:

- `surveys_df[0:1]` - `surveys_df[:4]` - `surveys_df[:-1]`What happens when you call:

- `surveys_df.iloc[0:4, 1:4]`

Solution - Range¶

# Solution - Range - #1 (a)

surveys_df[0:1]

# Solution - Range - #1 (b)

surveys_df[:4]

# Solution - Range - #1 (c)

surveys_df[:-1]

# Solution - Range - #2

surveys_df.iloc[0:4, 1:4]

Subsetting Data using Criteria¶

We can also select a subset of our data using criteria. For example, we can

select all rows that have a year value of 2002:

surveys_df[surveys_df.year == 2002].head()

Or we can select all rows that do not contain the year 2002:

surveys_df[surveys_df.year != 2002]

We can define sets of criteria too:

surveys_df[(surveys_df.year >= 1980) & (surveys_df.year <= 1985)]

Python Syntax Cheat Sheet¶

Use can use the syntax below when querying data by criteria from a DataFrame. Experiment with selecting various subsets of the "surveys" data.

- Equals:

== - Not equals:

!= - Greater than, less than:

>or< - Greater than or equal to

>= - Less than or equal to

<=

Challenge - Queries¶

Select a subset of rows in the

surveys_dfDataFrame that contain data from the year 1999 and that contain weight values less than or equal to 8. How many rows did you end up with? What did your neighbor get?(Extra) Use the

isinfunction to find all plots that containPBandPLspecies in the "surveys" DataFrame. How many records contain these values?

You can use the isin command in Python to query a DataFrame based upon a

list of values as follows:

surveys_df[surveys_df['species_id'].isin([listGoesHere])]

Solution - Queries¶

## Solution - Queries #1

surveys_df[(surveys_df["year"] == 1999) & (surveys_df["weight"] <= 8)]

# when only interested in how many, the sum of True values could be used as well:

sum((surveys_df["year"] == 1999) & (surveys_df["weight"] <= 8))

# Solution - Queries #2

surveys_df[surveys_df['species_id'].isin(['PB', 'PL'])]['site_id'].unique()

# To get number of records

surveys_df[surveys_df['species_id'].isin(['PB', 'PL'])].shape

Extra Challenges¶

(Extra) Create a query that finds all rows with a weight value greater than (

>) or equal to 0.(Extra) The

~symbol in Python can be used to return the OPPOSITE of the selection that you specify in Python. It is equivalent to is not in. Write a query that selects all rows with sex NOT equal to 'M' or 'F' in the "surveys" data.

sum(surveys_df["weight"]>=0)

surveys_df[~surveys_df["sex"].isin(['M', 'F'])]

Using masks to identify a specific condition¶

A mask can be useful to locate where a particular subset of values exist or

don't exist - for example, NaN, or "Not a Number" values. To understand masks,

we also need to understand BOOLEAN objects in Python.

Boolean values include True or False. For example,

# Set x to 5

x = 5

# What does the code below return?

x > 5

# How about this?

x == 5

Extra Challenges - Putting it all together¶

Create a new DataFrame that only contains observations with sex values that are not female or male. Assign each sex value in the new DataFrame to a new value of 'x'. Determine the number of null values in the subset.

Create a new DataFrame that contains only observations that are of sex male or female and where weight values are greater than 0. Create a stacked bar plot of average weight by plot with male vs female values stacked for each plot.

- Count the number of missing values per column. Hint: The method .count() gives you the number of non-NA observations per column.

Solution Extra Challenges¶

# Solution extra challenge 1

new = surveys_df[~surveys_df['sex'].isin(['M', 'F'])].copy()

new['sex']='x'

print(len(new))

# We can verify the number of NaN values with

sum(surveys_df['sex'].isnull())

# Solution extra challenge 2

# selection of the data with isin

stack_selection = surveys_df[(surveys_df['sex'].isin(['M', 'F'])) &

surveys_df["weight"] > 0.][["sex", "weight", "site_id"]]

# calculate the mean weight for each site id and sex combination:

stack_selection = stack_selection.groupby(["site_id", "sex"]).mean().unstack()

# Plot inside jupyter notebook

%matplotlib inline

# and we can make a stacked bar plot from this:

stack_selection.plot(kind='bar', stacked=True)

Combining DataFrames with Pandas¶

In many “real world” situations, the data that we want to use come in multiple files. We often need to combine these files into a single DataFrame to analyze the data. The pandas package provides various methods for combining DataFrames including merge and concat.

To work through the examples below, we first need to load the species and surveys files into pandas DataFrames. Before we start, we will make sure that libraries are currectly installed.

import pandas as pd

surveys_df = pd.read_csv("surveys.csv",

keep_default_na=False, na_values=[""])

surveys_df

Concatenating DataFrames¶

We can use the concat function in pandas to append either columns or rows from one DataFrame to another. Let’s grab two subsets of our data to see how this works.

# Read in first 10 lines of surveys table

survey_sub = surveys_df.head(10)

# Grab the last 10 rows

survey_sub_last10 = surveys_df.tail(10)

# Reset the index values to the second dataframe appends properly

survey_sub_last10=survey_sub_last10.reset_index(drop=True)

# drop=True option avoids adding new index column with old index values

When we concatenate DataFrames, we need to specify the axis. axis=0 tells pandas to stack the second DataFrame under the first one. It will automatically detect whether the column names are the same and will stack accordingly. axis=1 will stack the columns in the second DataFrame to the RIGHT of the first DataFrame. To stack the data vertically, we need to make sure we have the same columns and associated column format in both datasets. When we stack horizonally, we want to make sure what we are doing makes sense (ie the data are related in some way).

# Stack the DataFrames on top of each other

vertical_stack = pd.concat([survey_sub, survey_sub_last10], axis=0)

# Place the DataFrames side by side

horizontal_stack = pd.concat([survey_sub, survey_sub_last10], axis=1)

Row Index Values and Concat¶

Have a look at the vertical_stack dataframe? Notice anything unusual? The row indexes for the two data frames survey_sub and survey_sub_last10 have been repeated. We can reindex the new dataframe using the reset_index() method.

Writing Out Data to CSV¶

We can use the to_csv command to do export a DataFrame in CSV format. Note that the code below will by default save the data into the current working directory. We can save it to a different folder by adding the foldername and a slash to the file vertical_stack.to_csv('foldername/out.csv'). We use the ‘index=False’ so that pandas doesn’t include the index number for each line.

# Write DataFrame to CSV

vertical_stack.to_csv('output/out.csv', index=False)

Check out your working directory to make sure the CSV wrote out properly, and that you can open it! If you want, try to bring it back into Python to make sure it imports properly.

# For kicks read our output back into Python and make sure all looks good

new_output = pd.read_csv('output/out.csv', keep_default_na=False, na_values=[""])

Challenge - Combine Data¶

In the data folder, there are two survey data files: survey2001.csv and survey2002.csv. Read the data into Python and combine the files to make one new data frame. Create a plot of average plot weight by year grouped by sex. Export your results as a CSV and make sure it reads back into Python properly.

Joining DataFrames¶

When we concatenated our DataFrames we simply added them to each other - stacking them either vertically or side by side. Another way to combine DataFrames is to use columns in each dataset that contain common values (a common unique id). Combining DataFrames using a common field is called “joining”. The columns containing the common values are called “join key(s)”. Joining DataFrames in this way is often useful when one DataFrame is a “lookup table” containing additional data that we want to include in the other.

NOTE: This process of joining tables is similar to what we do with tables in an SQL database.

For example, the species.csv file that we’ve been working with is a lookup table. This table contains the genus, species and taxa code for 55 species. The species code is unique for each line. These species are identified in our survey data as well using the unique species code. Rather than adding 3 more columns for the genus, species and taxa to each of the 35,549 line Survey data table, we can maintain the shorter table with the species information. When we want to access that information, we can create a query that joins the additional columns of information to the Survey data.

Storing data in this way has many benefits including:

- It ensures consistency in the spelling of species attributes (genus, species and taxa) given each species is only entered once. Imagine the possibilities for spelling errors when entering the genus and species thousands of times!

- It also makes it easy for us to make changes to the species information once without having to find each instance of it in the larger survey data.

- It optimizes the size of our data.

Joining Two DataFrames¶

To better understand joins, let’s grab the first 10 lines of our data as a subset to work with. We’ll use the .head method to do this. We’ll also read in a subset of the species table.

# Read in first 10 lines of surveys table

survey_sub = surveys_df.head(10)

### Download speciesSubset.csv file from web

import urllib.request

url = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/nils-holmberg/sfac-py/main/csv/speciesSubset.csv'

urllib.request.urlretrieve(url, 'speciesSubset.csv')

# Import a small subset of the species data designed for this part of the lesson.

# It is stored in the data folder.

species_sub = pd.read_csv('speciesSubset.csv', keep_default_na=False, na_values=[""])

In this example, species_sub is the lookup table containing genus, species, and taxa names that we want to join with the data in survey_sub to produce a new DataFrame that contains all of the columns from both species_df and survey_df

species_sub.columns

survey_sub.columns

In our example, the join key is the column containing the two-letter species identifier, which is called species_id.

Now that we know the fields with the common species ID attributes in each DataFrame, we are almost ready to join our data. However, since there are different types of joins, we also need to decide which type of join makes sense for our analysis.

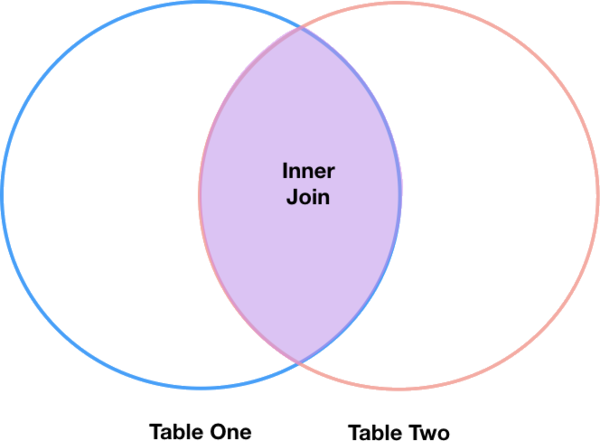

Inner Joins¶

The most common type of join is called an inner join. An inner join combines two DataFrames based on a join key and returns a new DataFrame that contains only those rows that have matching values in both of the original DataFrames.

Inner joins yield a DataFrame that contains only rows where the value being joins exists in BOTH tables. An example of an inner join, adapted from this page is below:

The pandas function for performing joins is called merge and an Inner join is the default option:

merged_inner = pd.merge(left=survey_sub,right=species_sub, left_on='species_id', right_on='species_id')

# In this case `species_id` is the only column name in both dataframes, so if we skippd `left_on`

# And `right_on` arguments we would still get the same result

# What's the size of the output data?

merged_inner.shape

merged_inner

The result of an inner join of survey_sub and species_sub is a new DataFrame that contains the combined set of columns from survey_sub and species_sub. It only contains rows that have two-letter species codes that are the same in both the survey_sub and species_sub DataFrames. In other words, if a row in survey_sub has a value of species_id that does not appear in the species_id column of species, it will not be included in the DataFrame returned by an inner join. Similarly, if a row in species_sub has a value of species_id that does not appear in the species_id column of survey_sub, that row will not be included in the DataFrame returned by an inner join.

The two DataFrames that we want to join are passed to the merge function using the left and right argument. The left_on='species' argument tells merge to use the species_id column as the join key from survey_sub (the left DataFrame). Similarly , the right_on='species_id' argument tells merge to use the species_id column as the join key from species_sub (the right DataFrame). For inner joins, the order of the left and right arguments does not matter.

The result merged_inner DataFrame contains all of the columns from survey_sub (record id, month, day, etc.) as well as all the columns from species_sub (species_id, genus, species, and taxa).

Notice that merged_inner has fewer rows than survey_sub. This is an indication that there were rows in surveys_df with value(s) for species_id that do not exist as value(s) for species_id in species_df.

Left Joins¶

What if we want to add information from species_sub to survey_sub without losing any of the information from survey_sub? In this case, we use a different type of join called a “left outer join”, or a “left join”.

Like an inner join, a left join uses join keys to combine two DataFrames. Unlike an inner join, a left join will return all of the rows from the left DataFrame, even those rows whose join key(s) do not have values in the right DataFrame. Rows in the left DataFrame that are missing values for the join key(s) in the right DataFrame will simply have null (i.e., NaN or None) values for those columns in the resulting joined DataFrame.

Note: a left join will still discard rows from the right DataFrame that do not have values for the join key(s) in the left DataFrame.

A left join is performed in pandas by calling the same merge function used for inner join, but using the how='left' argument:

merged_left = pd.merge(left=survey_sub,right=species_sub, how='left', left_on='species_id', right_on='species_id')

merged_left

The result DataFrame from a left join (merged_left) looks very much like the result DataFrame from an inner join (merged_inner) in terms of the columns it contains. However, unlike merged_inner, merged_left contains the same number of rows as the original survey_sub DataFrame. When we inspect merged_left, we find there are rows where the information that should have come from species_sub (i.e., species_id, genus, and taxa) is missing (they contain NaN values):

merged_left[ pd.isnull(merged_left.genus) ]

These rows are the ones where the value of species_id from survey_sub (in this case, PF) does not occur in species_sub.

Other join types¶

The pandas merge function supports two other join types:

- Right (outer) join: Invoked by passing

how='right'as an argument. Similar to a left join, except all rows from therightDataFrame are kept, while rows from the left DataFrame without matching join key(s) values are discarded. - Full (outer) join: Invoked by passing

how='outer'as an argument. This join type returns the all pairwise combinations of rows from both DataFrames; i.e., the result DataFrame willNaNwhere data is missing in one of the dataframes. This join type is very rarely used.

Extra Challenge 1¶

Create a new DataFrame by joining the contents of the surveys.csv and speciesSubset.csv tables. Then calculate and plot the distribution of:

- taxa by plot

- taxa by sex by plot